A Nation Addicted to Hope: From Democracy to Gen Z Revolt

Nepal is not poor in aspiration. It is poor in fulfillment.

For more than three decades, every political shift has carried a promise of national rebirth. Every election has sounded like a reset button. Yet the country still wrestles with the same questions: jobs, dignity, stability, and trust.

This is the story of Nepal’s recurring hope — and the betrayals that followed.

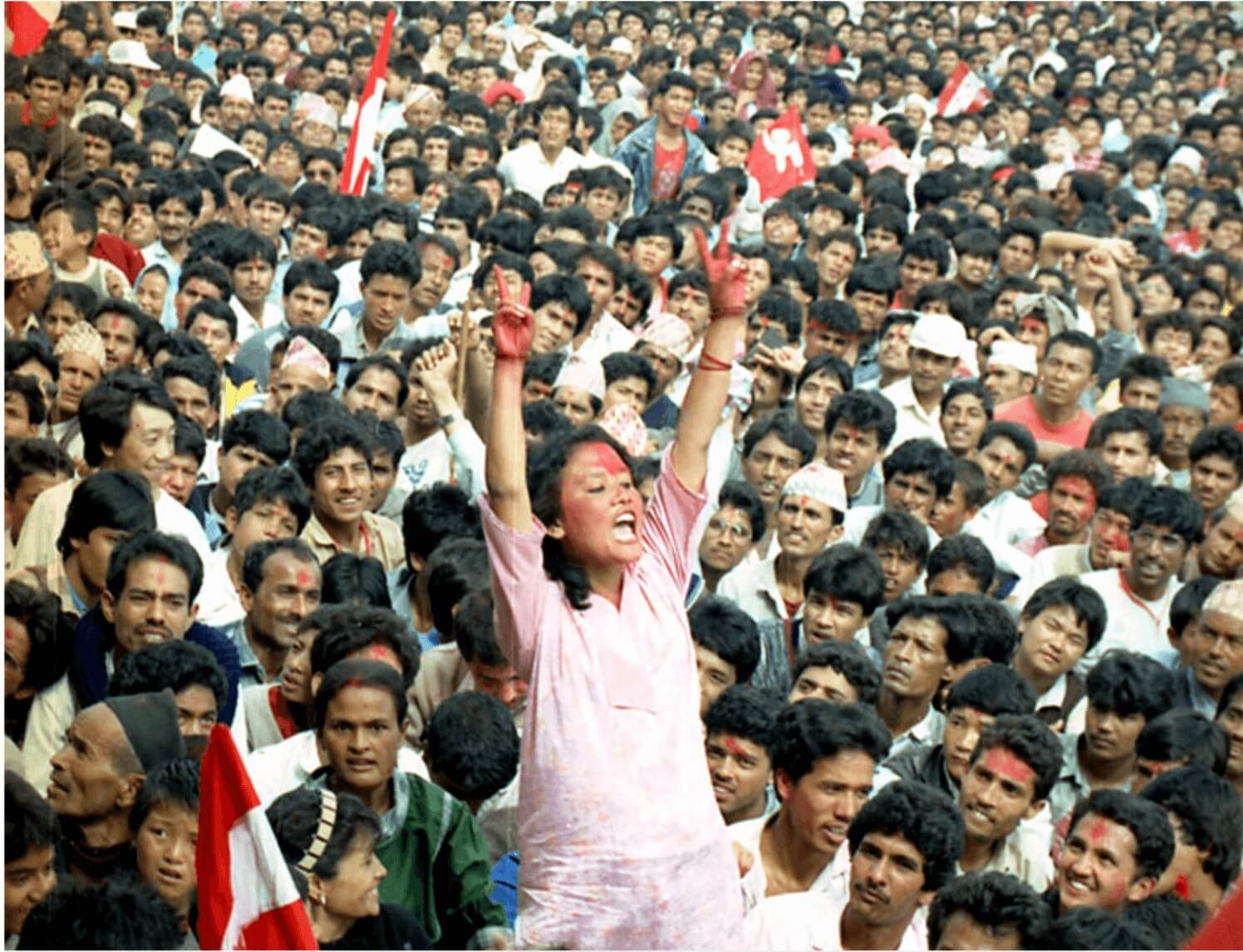

1990: Democracy and the Promise of Nepali Congress

The 1990 People’s Movement restored multiparty democracy after three decades of Panchayat rule. Citizens believed political freedom would unlock economic transformation. The early 1990s reforms liberalized trade, opened markets, and encouraged private enterprise.

Expectation: Institutional democracy, clean governance, market-led growth, stability.

Reality: Frequent government changes (over a dozen governments in the 1990s), factionalism, corruption scandals, and widening rural-urban disparity. By 1996, a violent insurgency had begun.

Democracy arrived. Delivery faltered.

The first betrayal was not of ideology — it was of performance.

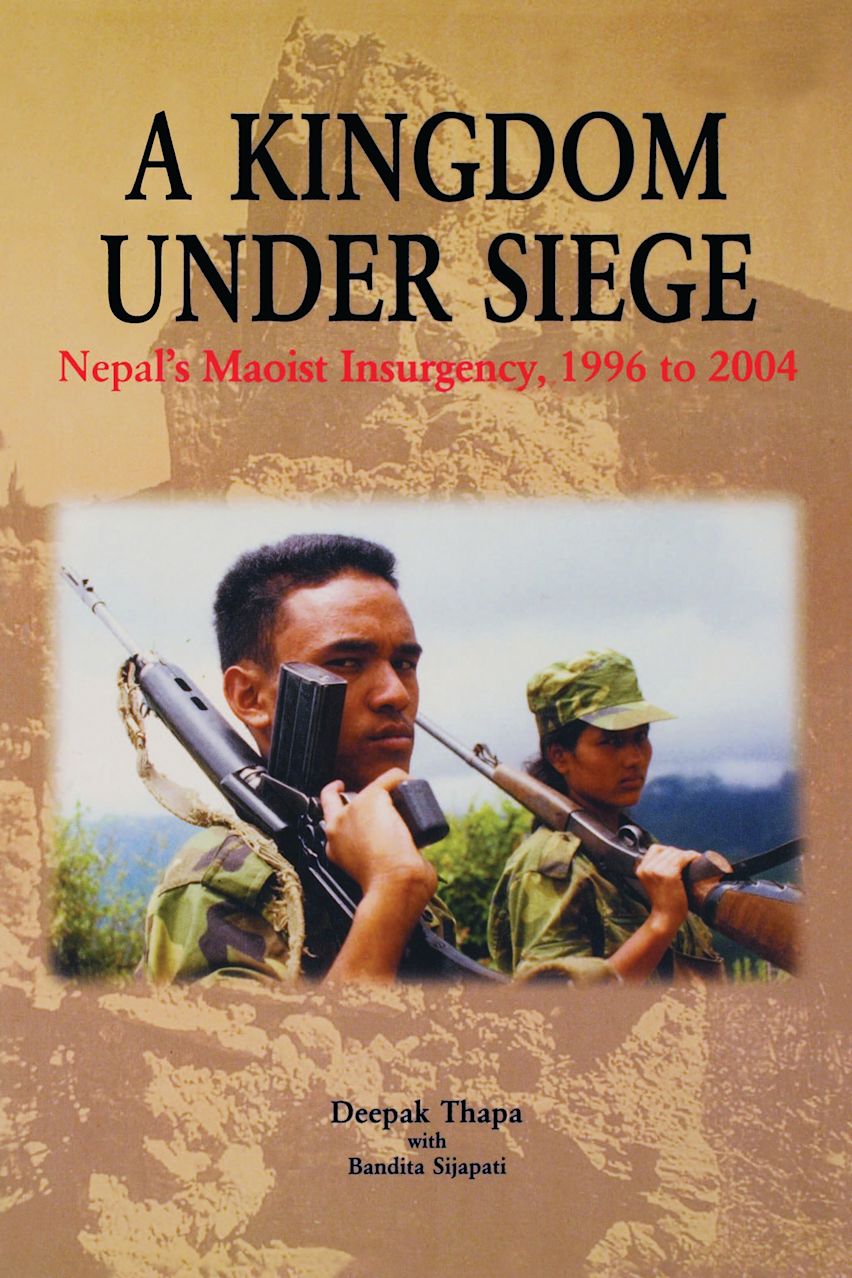

1996–2008: Revolution, Republic, and the Rise of Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre)

The Maoist insurgency (1996–2006) reframed national imagination around social justice, inclusion, and structural change. The 2006 Comprehensive Peace Accord and the 2008 declaration of a republic marked historic milestones.

Expectation: End of feudal hierarchies, inclusion of marginalized groups, republican restructuring, a new Nepal.

Reality: Prolonged constitution-writing (2008–2015), power-sharing deadlocks, integration controversies, and the normalization of revolutionary leaders into conventional political actors.

Inclusion advanced in law and representation. But governance capacity, economic restructuring, and industrial transformation lagged. The revolution promised structural change; politics delivered transactional coalitions.

The second betrayal was of transformation.

2015–2017: Stability, Nationalism, and Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist–Leninist)

After years of instability, the promulgation of the 2015 Constitution and the 2017 left alliance victory generated one of the largest post-conflict mandates.

Expectation: Political stability, infrastructure push, policy continuity, assertive sovereignty, faster growth.

Reality: Party unification collapsed into splits; parliament dissolution controversies deepened polarization; federalism faced coordination and capacity constraints.

Meanwhile, structural economic signals persisted:

Remittances consistently accounted for roughly a quarter of GDP in recent years.

Youth migration surged; hundreds of thousands of labor approvals are issued annually.

Private investment remained cautious; industrial growth modest.

Nepal’s standing in global corruption perception indices remained mid-to-low tier.

The third betrayal was of stability.

2022 Onward: Disruption — Rastriya Swatantra Party and Balendra Shah

The 2022 elections signaled a rupture. A new party surged into Parliament. An independent candidate won the capital’s mayoral seat. For many, this was not ideological — it was generational.

Expectation: Anti-corruption governance, meritocracy, administrative efficiency, performance over patronage.

Early Signals: Assertive municipal enforcement, sharper public communication, and a visible rejection of old party hierarchies.

But structural constraints remain:

Bureaucratic inertia and legal limits on executive action.

Coalition arithmetic at the federal level.

Federal-provincial-local coordination gaps.

An economy still heavily dependent on remittance inflows and import consumption.

The fourth test is whether disruption becomes institutional reform — or another personality-driven cycle.

The Gen Z Revolt: Electoral, Digital, Impatient

This generation grew up amid instability, saw peers depart for Gulf and OECD labor markets, and compares domestic governance with global standards in real time.

They reject:

Blind party loyalty

Patronage networks

Ideology without measurable results

They demand:

Transparency

Service delivery

Accountability dashboards

Time-bound execution

This revolt is not violent. It is narrative-driven, data-conscious, and ballot-based. It is the most consequential political shift since 2006 — because it is cultural.

Across cycles, the fundamentals have remained stubborn:

Employment Pressure: A young labor force with limited high-productivity absorption domestically.

Migration Dependence: Large-scale out-migration as a safety valve for unemployment and income gaps.

Remittance Reliance: Roughly one-quarter of GDP in recent years — stabilizing households, but masking structural weaknesses.

Governance Perception: Persistent public concern over corruption and policy inconsistency.

Policy Discontinuity: Frequent government changes interrupt long-term reform.

Citizens were promised industrialization, jobs at home, clean governance, and stability. What they received was incrementalism.

The Pattern We Refuse to Admit

Crisis erupts.

A new political force rises.

Hope peaks.

Structural resistance stalls reform.

Leaders normalize into the system.

Disillusionment spreads.

The search begins again.

We do not suffer from lack of leaders.

We suffer from weak institutions and short political memory.

Conclusion:

Nepal does not need another savior.

It needs rule-bound governance where no savior is necessary.

If hope continues to be invested in personalities, it will continue to be betrayed. If it shifts toward demanding institutional reform — civil service modernization, judicial efficiency, regulatory predictability, fiscal discipline, industrial policy coherence — then the cycle can finally bend.

Cautious optimism is justified because voters are more aware than ever. But optimism without institutional redesign is sentiment, not strategy.

Nepal’s greatest strength has always been its people’s refusal to give up. From 1990 to 2022, the ballot has remained an instrument of renewal.

But renewal must evolve. Hope must graduate from emotion to enforcement — from slogans to systems.

If this generation converts frustration into sustained civic pressure, performance metrics, and intolerance for corruption — then relief will not come as a dramatic revolution. It will arrive as steady reform.

And perhaps, for the first time, Nepal will not merely vote with hope.

It will govern with it.